On-demand economy- Testing the Strength of the Unions and Opening up Opportunities to more active Organizing

The on-demand economy has many synonyms or associated concepts, including the “access-“, “sharing-“, “gig-“, “peer-to-peer-“ or “collaborative-“ economy. The on-line on-demand economy is not a homogenous market- it characterized by 3 factors: “type of activity” (on-demand platforms are intermediating goods, services and combinations of both); “location of the activity” (some intermediated products/services are virtual, which creates in general a larger, more competitive market); “presence of both high- and low-skilled services on offer”.

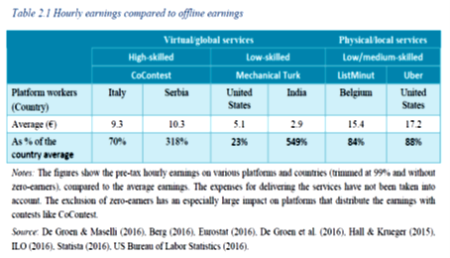

The on-demand economy is currently largely absent from official statistics. Most studies have, therefore, relied on surveys and case studies in order to analyse the size of the sector, how work is organised, who is working on what platforms and how much they earn. In Europe, the on-demand economy is still fairly small, despite its impressive growth.

Companies related to the on-demand economy: Uber , Airbnb , Upwork , TaskRabbit, Lyft, Instacart, Postmates, Handy

Which groups of workers are attracted by the sharing economy?

- those seeking flexible, part-time work

- labour-market outsiders (traditionally minorities, immigrants, young people and, to some degree, women).

- in the USA: relatively more often men, belonging to racial/ethnic minorities, living in urban areas and part of the millennial generation (aged 18 to 34).

- according to the Huws & Joyce (2016) surveys conducted in Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom: millennials; mostly men; people who are in most cases not earning all their income through a single online platform

How many workers are within the on-demand economy? The on-demand economy is (not yet) included as a separate category in official labour statistics, in which it is likely to be understated.

- According to De Groen & Maselli (2016), approximately 100,000 workers were active in the online on-demand economy in the EU at the end of 2015. They represent around 0.05% of the total employees in the EU, which is significantly less than the 0.4% to 1% of employees that is assumed to be participating in the US.

- The 2015 online survey by Burson-Marsteller , the Aspen Institute and TIME of 3,000 Americans found that 44% of the population is active on on-demand platforms (this includes both users and service providers).

- Huws & Joyce (2016) commissioned four online surveys that of more than 8,500 adults in Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The surveys focused only on crowd work or otherwise stated services with an important labour component intermediated through online platforms. Participation in all countries was around 11 to 12%, except for Austria where about 23% found work through platforms.

- The Eurobarometer found that 17% of EU citizens used platforms in early 2016 (both users and providers), although there is a large difference between countries.

- De Groen & Maselli (2016) estimated that there were roughly 100,000 active platform workers in the on-demand economy at the end of 2015, which is only 0.05% of the total employees in the EU.

On-demand economy brings negative effects for the workers:

- payment risk: lack of labour law protection, including the 1) guaranteed minimum wage or2) any payment for the performed work

- insufficient income in comparison to the income earned in traditional jobs

- constantly tracked performance

- easy dismissal: possible low rating by the platform client and possibility to be cut off by the platform

- lack of social protection : workers also have to pay the employer’s half of social security, which is a significant deduction from take-home pay

- demand for new skills to carry out new tasks: if it is difficult to obtain new skills, then the greater labour market polarization will be observed. Frey & Osborne (2016) estimate that almost half of all the new jobs require high skills- these include jobs such as data scientists, cloud architects and security analysts.

- maintaining a healthy work-life balance is becoming more challenging

- increased flexibility, which affects when, where and how tasks are performed

- blurring the line: are platform workers self-employed or employees

- collective bargaining typically took place between one union and one employer in the work place, but that digitalisation has substantially affected all of them: it is increasingly difficult to identify who the employees are and to organise them (changing unions), the concept of work place (changing work place) has drastically changed and employment relationships are changing shape (changing employers).

New forms of employment: The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound 2015) has analysed the ‘new forms of employment’ that are developing in Europe: - employee sharing, where an individual worker is jointly hired by a group of employers to meet the HR needs of various companies, resulting in permanent full-time employment for the worker;

- job sharing, where an employer hires two or more workers to jointly fill a specific job, combining two or more part-time jobs into a full-time position;

- interim management, in which highly skilled experts are hired temporarily for a specific project or to solve a specific problem, thereby integrating external management capacities in the work organisation;

- casual work, where an employer is not obliged to provide work regularly to the employee, but has the flexibility of calling them in on demand;

- ICT-based mobile work, where workers can do their job from any place at any time, supported by modern technologies;

- voucher-based work, where the employment relationship is based on payment for services with a voucher purchased from an authorized organisation that covers both pay and social security contributions;

- portfolio work, where a self-employed individual works for a large number of clients, doing small-scale jobs for each of them;

- crowd employment , where an online platform matches employers and workers, often with larger tasks being split up and divided among a ‘virtual cloud’ of workers;

- collaborative employment, where freelancers, the self-employed or micro enterprises cooperate in some way to overcome limitations of size and professional isolation.

The Trade unions and their practices need to be adapted to digitalisation :

- Still, in many countries, none or only limited modifications are being made to collective agreements, e.g. Germany . In Germany, IG Metall has changed its statutes so that the self-employed can join the union (similar examples also exist in Sweden).

In April 2015 IG Metall set up an advisory body on the future of work (Beirat ‘Zukunft der Arbeit’) composed of experts from business, academia and politics. The council is to meet twice a year, its task being to examine and identify at an early stage the changes taking place in the world of labour, so as to be in a position to devise options and seek answers to the key questions on the future of jobs. This is one way of providing practical accompaniment to the initiative of the employment and social affairs ministry in favour of quality employment in industry 4.0.

With regard to crowdworkers IG Metall has decided to create an internet site entitled FairCrowdWork Watch. The site enables crowdworkers to evaluate, in terms of working conditions and pay, the companies that use their services, to exchange views and experiences with one another, and to take advantage of legal advice supplied by IG Metall. This is one first attempt to organise these workers who are operating on a ‘parallel’ labour market that employs increasing numbers of totally atomised workers.

VER.DI has over a decade of experience supporting and representing the interests of self-employed persons, especially journalists.

IG Metall is open to self-employed members since January 1, 2016, with a focus on crowd- and platform-based workers. As of April 2017, self-employed members of IG Metall may receive insurance for legal costs up to EUR 100,000 in cases of legal disputes with clients. - In Finland, digitalisation appears to have diluted the hierarchy, pushing negotiations from the collective to the firm level.

- In Italy, it has been reported that digitalisation impacts collective bargaining in the sense that new topics are being drawn to the centre of debate: conciliation between private and working life, excessive stress and intensification of work due to technological devices, training opportunities, participation in the decision-making process.

In the US, for instance, several Uber driver demonstrations occurred and were aimed at protesting Uber’s reduced fares, tipping policy, five-star rating system and driver safety requirements (Kosoff, 2014). Uber drivers have even created associations such as the California App-Based Drivers Association or the Uber Drivers Network NYC. - In Poland on-demand economy businesses are creating an association for the sector;

- Sweden: Unionen has developed a plan to certify platforms for fair and socially sustainable working conditions.

- In the UK, sharing economy platforms have established the Sharing Economy UK (SEUK), an association that aims at promoting and representing sharing economy businesses and facilitating trust between providers and customers (Vaughan & Daverio, 2016).

The London-based Couriers and Logistics Branch of the Independent Workers of Great Britain is doing pioneering work defending the rights of workers in the British courier and logistics industry, including self-employed workers for major courier companies and food delivery companies such as Deliveroo and UberEats. About page.Join page.

IWW Leeds is raising funds to support 7 Deliveroo couriers who were punished or fired for organizing for better pay and more favorable contracts. - France: Volkswagen has put in place an arrangement whereby servers for professional smartphones go into sleep mode between 6.15 p.m. and 7 a.m. Daimler-Benz allows its workers to adopt an automatic reply arrangement for email messages sent during their holidays, a particular feature of which is to avoid a situation where the worker, on returning to work, in inundated by emails: either the messages received are redirected to another contact or the sender is asked to resend the message at a later date.

In France, the CFDT and the CFE-CGC signed, in 2014, a sectoral agreement on working time with the Fédération des syndicats des métiers de la prestation intellectuelle, du Conseil, de l’Ingénierie et du Numérique; this agreement too contains ‘right to disconnection’ provision. - Austria: The ÖGB supports the interests of crowdworkers. For Support, please contact crowdwork@oegb.at

The Austrian Chamber of Labor (Arbeiterkammer) ist doing pioneering work researching the working conditions of crowdworkers. - United States: The Teamsters 117 in Seattle and the New York Taxi Workers Alliance are doing pioneering work defending the rights of drivers working for Uber, Lyft, and other “transportation network companies.”

The Freelancers Union offers unique services for freelancers, including insurance and training, and worked with the City Council of New York to pass the landmark “Freelance Isn’t Free” Act, defending the rights of freelancers to ensure they get paid, in 2016.